A Model of Coexistence in the Canadian Rockies

Winding through the majestic Rocky Mountains, the Trans-Canada Highway serves as a vital artery connecting British Columbia and Alberta. Yet, as traffic intensified over the years, so too did incidents of wildlife-vehicle collisions. In response, Banff National Park became the birthplace of an innovative solution: the Banff Wildlife Crossings Project. Launched in 1978 by Public Works Canada, the project set out to address both public safety and ecological fragmentation. Its goal was to twin an 82-kilometer stretch of the highway from the park’s eastern entrance to the British Columbia border and, crucially, to implement a system of wildlife crossings to restore the natural migration paths disrupted by the roadway.Reimagining Infrastructure for Wildlife Safety

Launched in 1978 by Public Works Canada, the project set out to address both public safety and ecological fragmentation. Its goal was to twin an 82-kilometer stretch of the highway from the park’s eastern entrance to the British Columbia border and, crucially, to implement a system of wildlife crossings to restore the natural migration paths disrupted by the roadway.Reimagining Infrastructure for Wildlife Safety

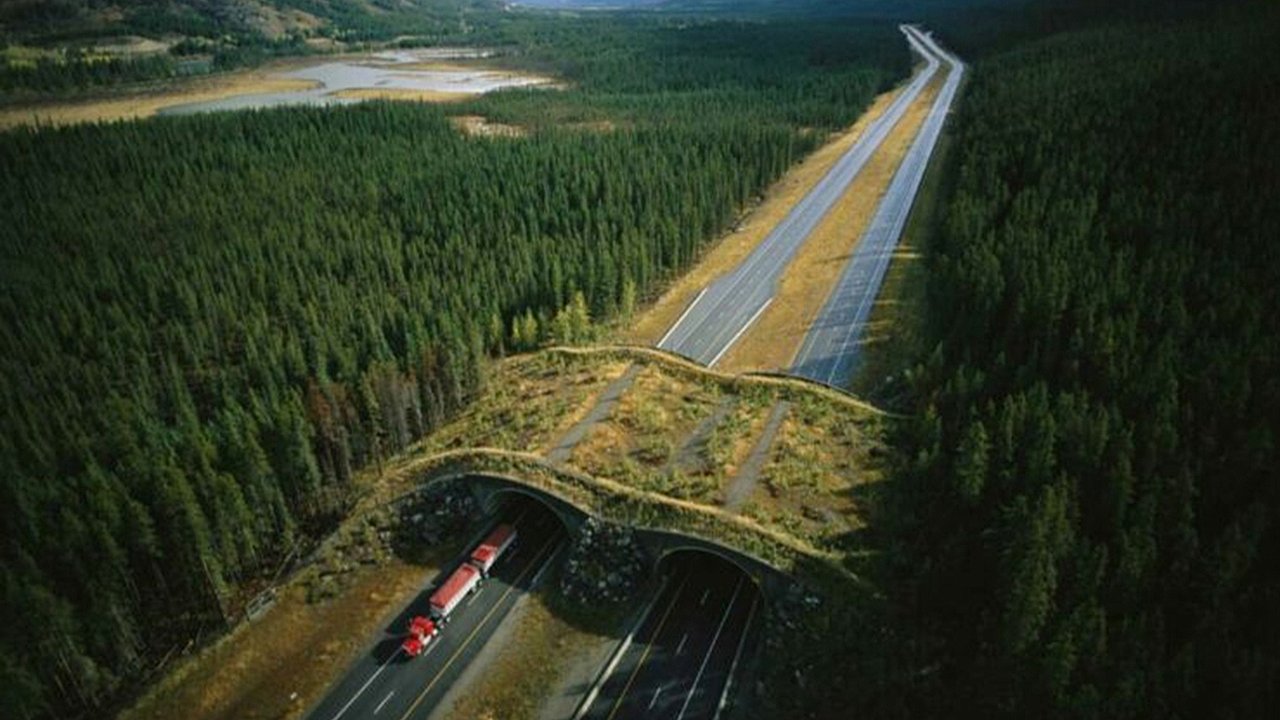

The first major step came in 1996 with the construction of two wildlife overpasses, each costing $1.5 million. These early successes paved the way—literally and figuratively—for an expanded network that now includes six overpasses and 38 underpasses strategically placed along the highway corridor.These crossings have proven remarkably effective. Overall, animal-vehicle collisions have dropped by more than 80%. The reduction is even more pronounced for species such as elk and deer, with incidents decreasing by over 96%. What may appear to drivers as ordinary highway bridges are, for wildlife, lifelines between habitats. Overpasses are covered with native soil and vegetation, blending seamlessly into the environment. Meanwhile, tall fencing guides animals toward the safe passageways and away from speeding traffic.A Diversity of Species, A Diversity of Needs

Decades of research and monitoring have confirmed the crossings’ success. At least 12 species—including wolves, lynx, coyotes, bears, deer, and wolverines—routinely use them. Elk were the first large mammals to explore the structures, doing so even before construction had concluded. Each species has demonstrated distinct preferences: grizzlies, moose, deer, and elk gravitate toward the open, natural feel of the overpasses, while more secretive animals like cougars and black bears opt for the shelter of the underpasses. Beyond enhancing safety, the crossings play a crucial ecological role by enabling gene flow between previously isolated populations. This helps sustain genetic diversity and resilience among wildlife, which is essential for long-term survival.Leading the Way in Road Ecology

Beyond enhancing safety, the crossings play a crucial ecological role by enabling gene flow between previously isolated populations. This helps sustain genetic diversity and resilience among wildlife, which is essential for long-term survival.Leading the Way in Road Ecology

The Banff Wildlife Crossings Project stands as a global beacon of innovation in road ecology. Researchers and policymakers from around the world have studied Banff’s model to replicate its success in their own regions—from tiger crossings in India to canopy bridges for howler monkeys in Costa Rica and safe pathways for jaguars in Argentina. The image of a wildlife overpass nestled in the Canadian Rockies, blanketed with greenery and set against a mountain backdrop, has become iconic. But more importantly, it symbolizes a shift in how we view infrastructure—not as a barrier to nature, but as a means of coexistence.Engineering for a Shared Future

The success of Banff’s wildlife crossings underscores what’s possible when engineering meets ecological awareness. It showcases the power of collaboration among government agencies, conservationists, scientists, and the public. More than a local achievement, it’s a powerful statement: even in the face of modern transportation demands, it is possible to design systems that protect both people and wildlife. A wildlife overpass in Banff national park, in the Canadian Rockies. Photograph: Ross MacDonald/Banff National ParkAs we look ahead to future development projects, Banff serves as a compelling reminder that thoughtful design and a commitment to coexistence can pave the way—literally—for a more sustainable and harmonious world.

A wildlife overpass in Banff national park, in the Canadian Rockies. Photograph: Ross MacDonald/Banff National ParkAs we look ahead to future development projects, Banff serves as a compelling reminder that thoughtful design and a commitment to coexistence can pave the way—literally—for a more sustainable and harmonious world.

Winding through the majestic Rocky Mountains, the Trans-Canada Highway serves as a vital artery connecting British Columbia and Alberta. Yet, as traffic intensified over the years, so too did incidents of wildlife-vehicle collisions. In response, Banff National Park became the birthplace of an innovative solution: the Banff Wildlife Crossings Project.

Launched in 1978 by Public Works Canada, the project set out to address both public safety and ecological fragmentation. Its goal was to twin an 82-kilometer stretch of the highway from the park’s eastern entrance to the British Columbia border and, crucially, to implement a system of wildlife crossings to restore the natural migration paths disrupted by the roadway.Reimagining Infrastructure for Wildlife Safety

Launched in 1978 by Public Works Canada, the project set out to address both public safety and ecological fragmentation. Its goal was to twin an 82-kilometer stretch of the highway from the park’s eastern entrance to the British Columbia border and, crucially, to implement a system of wildlife crossings to restore the natural migration paths disrupted by the roadway.Reimagining Infrastructure for Wildlife SafetyThe first major step came in 1996 with the construction of two wildlife overpasses, each costing $1.5 million. These early successes paved the way—literally and figuratively—for an expanded network that now includes six overpasses and 38 underpasses strategically placed along the highway corridor.These crossings have proven remarkably effective. Overall, animal-vehicle collisions have dropped by more than 80%. The reduction is even more pronounced for species such as elk and deer, with incidents decreasing by over 96%. What may appear to drivers as ordinary highway bridges are, for wildlife, lifelines between habitats. Overpasses are covered with native soil and vegetation, blending seamlessly into the environment. Meanwhile, tall fencing guides animals toward the safe passageways and away from speeding traffic.A Diversity of Species, A Diversity of Needs

Decades of research and monitoring have confirmed the crossings’ success. At least 12 species—including wolves, lynx, coyotes, bears, deer, and wolverines—routinely use them. Elk were the first large mammals to explore the structures, doing so even before construction had concluded. Each species has demonstrated distinct preferences: grizzlies, moose, deer, and elk gravitate toward the open, natural feel of the overpasses, while more secretive animals like cougars and black bears opt for the shelter of the underpasses.

Beyond enhancing safety, the crossings play a crucial ecological role by enabling gene flow between previously isolated populations. This helps sustain genetic diversity and resilience among wildlife, which is essential for long-term survival.Leading the Way in Road Ecology

Beyond enhancing safety, the crossings play a crucial ecological role by enabling gene flow between previously isolated populations. This helps sustain genetic diversity and resilience among wildlife, which is essential for long-term survival.Leading the Way in Road EcologyThe Banff Wildlife Crossings Project stands as a global beacon of innovation in road ecology. Researchers and policymakers from around the world have studied Banff’s model to replicate its success in their own regions—from tiger crossings in India to canopy bridges for howler monkeys in Costa Rica and safe pathways for jaguars in Argentina. The image of a wildlife overpass nestled in the Canadian Rockies, blanketed with greenery and set against a mountain backdrop, has become iconic. But more importantly, it symbolizes a shift in how we view infrastructure—not as a barrier to nature, but as a means of coexistence.Engineering for a Shared Future

The success of Banff’s wildlife crossings underscores what’s possible when engineering meets ecological awareness. It showcases the power of collaboration among government agencies, conservationists, scientists, and the public. More than a local achievement, it’s a powerful statement: even in the face of modern transportation demands, it is possible to design systems that protect both people and wildlife.

A wildlife overpass in Banff national park, in the Canadian Rockies. Photograph: Ross MacDonald/Banff National ParkAs we look ahead to future development projects, Banff serves as a compelling reminder that thoughtful design and a commitment to coexistence can pave the way—literally—for a more sustainable and harmonious world.

A wildlife overpass in Banff national park, in the Canadian Rockies. Photograph: Ross MacDonald/Banff National ParkAs we look ahead to future development projects, Banff serves as a compelling reminder that thoughtful design and a commitment to coexistence can pave the way—literally—for a more sustainable and harmonious world.